There’s an amusing running joke in The Tough Guide to Fantasyland, Diana Wynne Jones’ faux-encyclopedia/travel guide to fantasy tropes: the entry for “BATH” warns travelers to “take care, however. Baths are the occasion for SEX with one of more of your FELLOW TRAVELERS. No matter how irritating you have found her/him up to then, after or during the Bath you will find her/him irresistible. It is probably something in the WATER.” Later entries for SEX and VIRGIN include a note to “see also BATH.” Travel through the fantasy genre itself, and you’ll find that often sex has been reduced to little more than a tired, predictable cliché, usually at the expense of the fairer sex. Female characters are routinely raped in the name of “character development.” Or femme fatales use their wiles to manipulate men. That’s assuming readers even get the female perspective; as with the erotically charged “bath”, sex in fantasy may serve as little more than a foregone conclusion for the male hero’s relationship arc, at which point the action “fades to black” and whatever happens after seems to be of no import.

Then there’s Jacqueline Carey’s epic fantasy Kushiel’s Dart, which is about sex from the cover: a topless woman artfully concealing her nakedness while showing off the inked marque that represents her indentured servitude and her service to the goddess of pleasure. It’s about sex from page 1, in which Phèdre nó Delaunay, “a whore’s unwanted get,” is sold into bondage in the Court of Night-Blooming Flowers, facing a similar, if tedious, future as just another warm body in a brothel. It’s still about sex 700 pages later, when Phèdre, now a famous courtesan, channels the goddess Naamah by offering up her body to foreign rulers to avert war. But Kushiel’s Dart rises above other entries in the genre by first demystifying sex and then tapping into the nuances of the act and how it affects the characters’ every other action: celebrations, murders, alliances, battles, and victories.

In Terre d’Ange, sex is simultaneously no big deal and the biggest deal. Seeking out and enjoying pleasure is so ingrained in society that a visit to the Night Court provokes little more than good-natured jabs. Courtesans are among the most revered members of society because what they do is literally a sacred act. And whether you’re lying with your life partner or a partner for a night, very little is taboo.

I like to describe Terre d’Ange as the trifecta of non-heteronormativity: queer, kinky, and nonmonogamous. Sexual orientation in Phèdre’s world is neither demonized nor agonized over; D’Angelines love who they love, and most seem to be bisexual, though there are certainly those who prefer one gender over the other. Not everyone in the series is into BDSM, but considering this is from Phèdre’s point of view, we meet a lot of doms. In keeping with the kingdom’s founding precept of “love as thou wilt,” many D’Angelines seem to be open to the notion of multiple partners at any given time; each couple, it would seem, have their own definitions of commitment, from a closed marriage to multiple situational “friends with benefits” arrangements.

The book is not saying that everyone should embody all three of these qualities; it simply offers them up as options.

Despite how much sex pervades D’Angeline culture, Kushiel’s Dart is not what the fanfiction community has termed a Porn Without Plot (PWP). First and foremost, the series is about the descendants of angels/gods playing out their mortal games while fielding occasional interference from the angels who founded their land. Those human concerns center on the game of thrones, the interplay between courtly intrigue and clever spycraft. And Anafiel Delaunay hits upon the idea of training young courtesans, with their foundation of social etiquette and capacity for learning, in the covert arts and self-defense. By arming them with knowledge to dissemble and manipulate their patrons, as well as the ability to defend themselves should situations go awry, Delaunay molds Phèdre and her foster-brother Alcuin into spies, gathering intel on the peers of the realm during their assignations. It’s kind of genius, actually—in a society as sexualized as Terre d’Ange, it’s the equivalent of hiding in plain sight.

Political intrigue, fancy feasts, sumptuous balls, wars, godly interference… What’s brilliant about Kushiel’s Dart is that it doesn’t stray too far from these traditional fantasy tropes; Carey simply imbues those tropes with a sexual dimension. Consider how fantasy is full of mortals suffering through well-intentioned gifts from the gods, fairies, or prophecies; think of Ella Enchanted’s eponymous heroine, unable to fight her compulsion to follow orders, or Chosen One Harry Potter, whose mighty reputation not only precedes him but actively trips him up in almost every single interaction. Why should Phèdre’s case be any different? Her inconveniences are just more titillating, like when a tattoo session leaves her writhing on the table in bliss from the sharp needles. Or how she occasionally hears the beating of bronze wings, an indicator that her god Kushiel has turned his fierce, masked gaze on her, his anguisette.

But once sex is introduced, it colors how a character, how a piece of work, is perceived. With this emphasis in everything from the worldbuilding to the major plot, er, climaxes, Kushiel’s Dart often gets unfairly lumped into romance, with Phèdre uncharitably written off as a shallow erotic fantasy of total submission. When sex is seemingly the most important thing, or at least the most obvious thing, about a woman, it runs the risk of stripping her down to a one-dimensional being, a stock character to be easily categorized and managed. The thing is, Phèdre is a fantasy—she’s the fantasy of a woman who can be a sexual being and still be more than that.

Phèdre can enjoy the hell out of sex without being a slut. Her affinity for being whipped has no bearing on her ability to master foreign tongues. During an assignation, she can tremble with the humiliation of enjoying being depraved, but during a diplomatic meeting she can look her fellow ambassador in the eyes unflinching, and these things are not mutually exclusive. What Phèdre does in the bedchamber does not have any bearing on her competency in a nonsexual setting.

Now, to be clear, Phèdre’s bedroom romps do have quite a bit of bearing on the plot itself. Her assignations both yield the information Delaunay desires while also putting her into a number of harrowing situations where she’s helpless at the hands of people who would have little difficulty staging a murder in the form of an especially rough session taken too far. And let’s not forget the latter portion of Dart that can be summed up as “Phèdre’s magical vagina rallies the troops to her side.” While she later matures into a more nuanced ambassador, her early days of negotiating do involve a fair amount of physical follow-through.

Yet before you go shouting “Mary Sue!”, Phèdre’s position as Kushiel’s earthly tool keeps her from being impossibly perfect and getting everything she wants. Pricked as she is by Kushiel’s Dart, she’s often at the mercy—in a very unsexy, not-fun way—of whatever master plan the gods have not seen fit to let her in on. And despite her beauty and fast-healing skin that make her such an ideal anguisette, there’s also no small measure of arrogance; barely out of her teens in Dart, Phèdre regularly overestimates her ability to get out of thorny situations. And sometimes she’s just a complete idiot in love, utterly failing Delaunay’s training by letting the sex get the better of the spying.

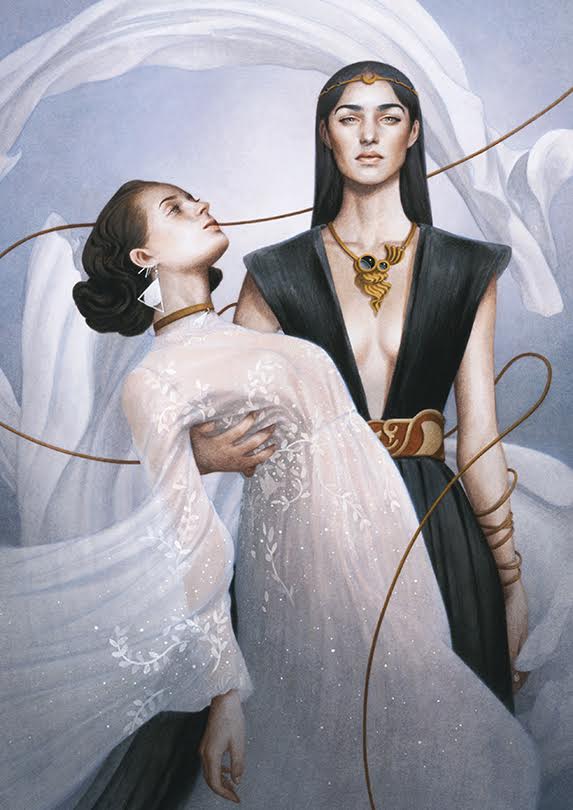

Think of your favorite hero/nemesis matchups: Batman/Joker. Sherlock Holmes/Moriarty. Professor X/Magneto. The Doctor/The Master. These pairings are distorted mirror images of one another, or they’re duos who started out with the same background or powers that, if not for a key point of divergence, might have ended up on the same side. Phèdre and Melisande Shahrizai are no different: both clever, sharp-witted, with a love of covertcy and, yes, sex. Both are touched by Kushiel, but in inverse ways: Where Phèdre was “blessed” with an anguisette’s capacity for submission, House Shahrizai are scions of Kushiel, both nature and nurture making them doms with a sadistic streak.

You know what makes these two such a compelling pair? You guessed it—the sexual tension. Fans will joke about ’shipping these other heroes and nemeses, scrutinizing their interactions for any possible shred of subtext. Phèdre/Melisande is supertext, baby.

While Alcuin gets his fair share of intel from the bedchambers of D’Angelines, Phèdre is Delaunay’s greatest triumph. If not for the red mote in her eye, Delaunay wouldn’t have plucked her out of obscurity. Because not only did he see a courtesan-spy in the making, but he also saw the subterfuge in her submission. Her patrons believe that she will be so distracted by the interweaving of pain and pleasure that they will have complete control over her, from the moment she steps through their doors to the moment they release her. Instead, they are the ones distracted, failing to notice the gears turning in her mind even as she takes humiliating lashes of the whip and dangerous branding from a red-hot poker.

Even Melisande, even Phèdre’s greatest love (well, one of them) and greatest nemesis, falls prey to this assumption that one who is submissive has no control. But there’s a difference, as Phèdre’s dear friend Hyacinthe points out, between submission and total surrender: “That which yields is not always weak.”

Carey normalizes all manner of queer sexualities in Kushiel’s Dart, crafting an open-minded foundation within which to set this compelling tale. Would that this kind of nuanced representation be the baseline for all fantasy stories. But the most remarkable part of Phèdre’s saga is that it’s about a sexual woman who is continually underestimated and proves, over and over, that she is worthy of so much more.

For a limited time, get a free ebook of Kushiel’s Dart by joining the Tor.com eBook Club! Offer expires July 19th at 11:59 pm, US & Canada only.

Natalie Zutter is so excited you’re all picking up Kushiel’s Dart. Talk courtesan-spies and sex-positive fantasy with her on Twitter!

Thank you for a very perceptive review. I read this book a long time ago, you’ve tempted me to re-read.

You had me until “unfairly lumped into romance.”

Why is there always a need to bash one of the most popular genres on the planet?

I expect more from Tor.

So my wife picked up this book a long time ago, on a supermarket shelf in the “Romance” section. She likes them because, quote, “I can turn my brain off with a dumb romance book”, unquote.

I glanced at the cover, nodded politely, and went on my way. Dumb romance books are not to my taste.

Tor just put this out as the ebook-of-the-month, which struck me as odd, because as far as I knew, Tor doesn’t make a habit of publishing “dumb romance books”. So what the heck, I’ll give it a try, worst-case scenario I can feel vindicated by mashing ‘delete’, right?

WHAT IS THIS I DON’T EVEN WHAT.

This is not a “dumb romance book”. It’s got a lot of sex — a lot of sex not to my tastes, even! — and not a bit of it is unnecessary to the plot. Speaking of the plot, it’s riveting. I picked up the book after work and didn’t put it down until almost 5 am the next morning.

I know you’re not supposed to judge a book by its cover. Mea culpa. This was an amazing read.

I liked this book but did not love it… The sex scenes are fun but the first third of the book was too much political intrigue for me.. I admit I was a little glad when Phedre was taken by the Skaldi since the plot picked up some action/swordplay/magic. Still the book is a little rapey dont you think, especially after she is kidnapped, but its ok because she enjoys it???

@@.-@ – No, it is most assuredly not OK “because she enjoys it”. In fact, the heroine constantly comments on how she hates how her body betrays her – her blessing becomes a curse, she’s forced to endure pleasure at being raped, and she absolutely loathes it.

Do we really want to glamorize sexual slavery? ‘Sold into bondage’ doesn’t sound like a Good Thing.

@6 – ‘sold into bondage’ is not a good thing in general; sex has very little to do with the good or bad of it in this setting. Phedre is sold because her parents wanted financial security, and they are never heard from again, save that Phedre defines herself as ‘unwanted’ through her childhood, making Delaunay that much more a potent father figure. The brothel that Phedre is indentured to cannot force her to take up prostitution either, if she’d refuse it; it is simply not looked down upon and the simplest way of paying the bond.

So she’s a bondslave but can’t be forced into prostitution?

@8: “So she’s a bondslave but can’t be forced into prostitution?”

That’s correct. The central tenet of D’Angeline religion is love as thou wilt, which necessarily means that neither Phedre nor anyone else sold into indenture at the Night Court can be forced into service to Naamah as a courtesan. There are opportunities in the Houses to “make one’s marque” (that is to say, pay off one’s indenture) doing other things: adepts from Bryony House are often involved in finance, for example, and Phedre has a meaningful (and nonsexual) relationship with a fashion designer from one of the Houses later in the series.

eh, hem. “Unfairly categorized as romance”–please refrain from trash talking another genre to hold up your own. Either Fantasy and SF can stand on its own without measuring it againt the biggest, most popular selling genre or it can’t.

I was excited to see a fantasy attempt a sex positive book with a plot, something I’ve been reading in romance for a long time. I’ll have to check it out and see if it measures up.

@6, Kushiel’s Dart and the other other books in the trilogy take place during something that is, economically, not far from late Middle Age Europe. Chattel slavery or serfdom or both were pandemic in almost all pre-industrial societies (and chattel slavery existed in industrial plants, such as the Tredegar Iron Works in the ante-bellum South, so it was not precluded by industrialization). Phèdre was sold into something more resembling indentured servitude (or at least the idealization that is described in US high school history textbooks) than actual slavery, as, for one thing, slaves don’t have the right to buy their freedom. Regardless of this criticism — and I think you’ve got a valid point about Phèdre’s being sold, by her parents, into what they knew could be sexual servitude — Terre d’Ange probably has a generally better treatment of women than did real Europe at about that level of political and technological development (as I said, late Middle Age Europe).

Overall, I think Ms Carey’s worldbuilding was quite good. I really don’t know her process, but I think she very loosely modeled Phèdre on the legend of Mata Hari, as a spy who got secrets by seduction, then designed the culture where that would not end up with her spy learning nothing except that Private Jones had a spare $47 dollars, bad breath, and syphilis.

@3 you used the word “dumb” in front of the term “romance book” four times. Why you feel it’s a good idea to let the world know that you and your spouse think insulting things about another genre – one that is clearly much beloved by millions of readers – I have no idea. Personally I think most sports and action movies are profoundly dumb. But, I respect that millions of people love them, so I don’t go around writing ugly things about them in public forums. If you can’t bring yourself to show respect for another genre, at the very least consider showing respect for those who love it.

Something else I like about this series is that traumatic events are remembered, not dismissed and forgotten just because they occurred in an earlier book. They become a part of that character and consistently carry forward with him/her.

@@@@@ 11, Slaves could buy their freedom under many systems, it was quite common under the Romans where it was made possible by slaves practicing crafts and professions and being allowed by custom to retain part of their earnings.

Indentured servitude is theoretically better than slavery because it’s set up to allow for repayment. But as you say it has often been abused. For example the accomplished courtesans in eastern systems of upper class prostitution could theoretically repay their owners and buy their freedom but in practice costs were piled on making it all but impossible Usually the only way out was to be bought by a customer

Just to add (again) to all the other followups and well-detailed comments regarding indentured servitude – the author does set up Terra d’Ange as what looks like an idealized society, and systems like the Night Court’s indenture mostly work as intended and with as much benevolence as people bring to it. That said, abuses do happen and are held up as crimes and heresies (Hyacinthe’s mother, Favrielle later in the series), and Phedre works to correct these whenever she can. This isn’t even getting into the contrast to other cultures Phedre ends up in, where other systems (including outright slavery, which Phedre endures) contain no such benevolence, and are portrayed as the hells they are. One of Phedre’s mentors earliest comments is that it is always wrong to treat people as chattel, and despite Phedre’s origin story having it’s shadows, this moral is held up very strongly through all of Carey’s books.

Selling children is always a Bad Thing. Adults willingly entering into a contract is of course a different matter. A society that permits the former is no Utopia.

Terre d’Ange is not a utopia, and I don’t think it’s really intended to be. There are too many tensions and conflicts in the country for that. What Carey constructed is a country that is medieval in its trappings, but relatively (and thoughtfully) modern in its sensibilities. It’s a feudal state, and its economic and political systems reflect that, but it is not Westeros; women stand on more or less equal footing in Terre D’Ange, if not elsewhere. Accordingly, prohibitions against rape and sexual freedom are both the sacred and civil law of the land.

The central conceit of Phèdre’s power is difficult for me to grapple with sometimes–she is a sacred submissive who sometimes has to endure rape. There is never any doubt that the rapists are wrong, but Phèdre keeps getting put in (and putting herself in) situations where this is still a risk. I guess it’s to the books’ credit that the characters have trouble with these issues too.

To be fair a society that doesn’t have tensions and conflicts – and failures of justice – would not only be boring to read about but impossible. Humans are famous for messing up.

@11, true, in many systems, slaves could buy their freedom, but there was nothing like a mandate on permitting them to do so. Ideally, indentured servants had a guaranteed way of buying their freedom ( and any children born to a woman under indenture would inherit the indenture until adulthood), but human nature being what it was, the people who owned the indenture would try to cheat to keep the person in servitude. In reality, in British North America, indentured servants were not treated that much better than slaves, and many did not live out their indenture.

Indentured servitude died out for a number of reasons, but I’m sure one reason race-based slavery was preferred was that the slaveowners could make a default assumption that a person of African* origin was a slave, but couldn’t make the assumption that a person of European origin was indentured, which made it much easier for an indentured servant to escape. .

* Native Americans were also enslaved, but it was possible for them to escape and merge with local Native American groups. Of course, the British settlers could — and did — sell enslaved Native Americans to places like sugar islands in the Caribbean.

This trilogy is pretty good and I enjoyed it as she is a compelling heroine. I did not enjoy the next trilogy so much as a it felt more like an anthology. This happened and then this happened and then this happened is the pace of the next trilogy, which felt strange to me.

Yay! My favorite books!

Great review, though I quibble a bit at the line

It’s still about sex 700 pages later, when Phèdre, now a famous courtesan, channels the goddess Naamah by offering up her body to foreign rulers to avert war

Phedre seduces the Twins of the Dalriada to coax them to war, not avert it.

The books are phenomenally consistent, IMO. The D’Angelines practice Elua’s tenet “Love as thou wilt”, but it goes beyond that. So long as people ACT out of love, they are acting in accordance with the desires of the Gods. Even those who have loves that inspire them to act in terrible ways, and still doing as the gods wish.

Carey also has a great gift for foreshadowing.

Carey is a phenomenal author with incredible world building that stays consistent throughout the series. This world isn’t anymore of an utopia then any other world. As you read the series, you will see war, kidnapping, slavery, torture, rape, and death. You will also see so many multitudes of love. There are 12 houses in the NIght Court with each house practicing a different form of love. There is love everywhere in Terra d’Ange. Rape is blasphemy in Terra d’Ange with the rapist being executed.

The scenes where Phedre is being super submissive has the standard dom/sub contract in them. She has a safeword which if she says it then the dom has to stop whatever he or she is doing. This is a built in part of her profession.

I love this series. Phèdre is so enjoyable precisely because she isn’t perfect- she makes bad choices, she is attracted to Melisandre (who makes a delightful antagonist), she’s arrogant and she’s still learning. The world she lives in isn’t perfect either, for reasons other people have already called out, but who would read it if there were no flaws?

<i>The thing is, Phèdre is a fantasy—she’s the fantasy of a woman who can be a sexual being and still be more than that.</i>

Yes, exactly!

The “slave who can’t be forced into prostitution” bit is more complex, and less ideal, as it is explored in latter books.

Children who are sold owe an indefinite debt to the person or institution they are sold to. They have to work for whomever they are sold to, until they collect enough money of their own to complete the tattoo on their back. They are not paid for their work, their owner is paid. They must collect the money for their tattoo from tips, and they are forbidden from negotiating for those tips, from refusing service to those who don’t tip, etc.

It is customary for clients to tip prostitutes. But those slaves who won’t work as prostitutes often find themselves doing work that does not involve customary tipping, and therefore unable to collect the money to pay for their tattoo and earn their freedom.

So while a slave cannot be “forced” into prostitution, a slave who wants to be free has little choice but to comply with the system of prostitution in order to earn their freedom. We see this with Phaedre’s foster-brother, who does not enjoy the prostitution, but who goes along with it, and who illegally negotiates for a large tip to earn his freedom from a particular client.

Phaedre is comfortable with sexual work, so the coercive nature of the system is downplayed in the books that directly feature her. But she doesn’t get to choose her clients, or decide when and how she will work, until she’s paid off her tattoo.

@24: “We see this with Phaedre’s foster-brother, who does not enjoy the prostitution, but who goes along with it, and who illegally negotiates for a large tip to earn his freedom from a particular client. “

Admittedly, it’s been a while since I’ve read Kushiel’s Dart, but I’ve read it a lot, and I don’t recall anything even hinting that it was *illegal* for Alcuin to make that demand of Bouvarre. And in fact, reviewing my ebook version (thanks, Tor!), the text is clear that Phedre is scandalized to realize that Alcuin has *chosen* to enter the service of Naamah to advance Delaunay’s agenda *despite* his deep distaste for it (which, by D’Angeline standards, is blasphemy, and is only partially redeemed because Alcuin has made that choice out of his own love for Delaunay), and that she believes that Delaunay would not have permitted it if he had known.

@25 – What other way did Aleuin have to earn his marque, and his eventual freedom? Delaunay had chosen that path for him, when he was just a child, and trained him to that task and no other. The amount of coercion is enormous. That he “loved” his owner and master does not make him less a slave. It speaks more to brainwashing – a child loving the adult who raised him, and being willing to do things he found distasteful for the master’s sake. The grooming that sexual abusers use on their child-victims comes to mind.

In latter books we see this more clearly, with secondary and tertiary characters who are owned by the Night Court, but who do not have the talent or desire to be prostitutes, being essentially trapped.

There is a polite face to this form of sexual slavery, that slaves have a “choice”, and many believe this, even some slaves, particularly one like Phedre, who does have such a calling. But when you look for options for children sold into this captivity, if they want to “chose” differently and still earn their freedom, it isn’t there. Just walking away and being free, choosing a trade and supporting yourself, isn’t an option, when you’re enslaved by a debt your parents placed on you.

Phaedre is an elite prostitute, and it takes her years to earn her freedom. How long would it take someone who doesn’t have her beauty and unique talents? What options does such a slave have, after spending their early adulthood working as a prostitute to earn their freedom, to start over in middle age? Who supports them, when they are no longer slaves to the Night Court, no longer young and attractive to be commanding better prices as prostitute, and not trained to another task?

The time it takes to earn a marque seems to be suspiciously timed to how long one can work successfully as a prostitute – once you’ve made your marque, you’re “free” and no longer the responsibility of the Night Court that owned you – but not necessarily able to support yourself, either.

If you aren’t by nature an elite prostitute, like Phaedre, the system is much more of a trap than she found it.

@26, perhaps it’s similar in length of term to the sort of indentured servitude common in the early settlement of British North America, where the terms of service were set to a finite term, typically, four to seven years, with the possibility of earlier redemption for someone whose earnings are greater than the norm. Also, it’s possible that Phèdre had a much higher purchase price to pay off: she was, after all, the first bearing the scarlet mote marking her as one of Namaah’s own. . Historically, there was a functional difference between “slavery” and “indentured servitude,” in that the latter had a guaranteed expectation that their term of service was finite, while the former did not, and that masters were, at least nominally, more restricted in what they could do to a slave.

Overall, I suspect the society portrayed in Kushiel’s Dart has a much more unpleasant underbelly that doesn’t get shown. Of course, Tolkien didn’t show the Shire’s farm laborers, who would have barely been earning enough to eat, nor did the Morte d’Artur show the serfs.

http://www.pbs.org/opb/historydetectives/feature/indentured-servants-in-the-us/

The Night Garden seems to me to be very similar to the organized prostitution you’d have found in Imperial China or Japan rather than the kind of indentures with which early American immigrants paid off their passage with so many years of labor.

In the Eastern Pleasure Houses the girl didn’t just have to pay off the money paid to her parents for her but the costs of her training, of her room and board, of her expensive costumes and jewelry, etc. etc. In other words the debt kept growing during her grooming and training and even after she started working. No wonder most never got free.

What we see is pretty dark.

Delauney asks Padre if she wants to be a prostitute, and dedicates her to that service, at the age of fourteen. When she’d had no training except that given in expectation that she would work for him as a prostitute and spy. She complains to her instructor that if she’d been in the Night Court, she would have started this work a year earlier (13) and already be paying to get her marque.

That’s too damn young, wit too few options to choose from to be considered “consent.”

The nature of the marque tattoo is telling. A completed tattoo signifies freedom. But one doesn’t save money and they buy their tattoo all at once. Slaves start getting marked as young as thirteen. And an incomplete tattoo serves as physical proof that one is a slave, making escape difficult, as your own body bears the mark of your “debt” – one that you didn’t choose, and one that you received no benefit from. Phaedra’s “debt” began when her mother was paid off, and grew when Delaney bought her, but she didn’t get a penny.

And even “earning” your freedom by completing your tattoo doesn’t mean you aren’t still financially trapped. For years, you will have worked with every penny you earn going into someone else’s pocket. Any extra you’ve gotten through gifts or tips you have not been able to save or invest for your future, instead having to pay the tattoo artist of your owner’s choice. You may end up free, but without resources to support yourself.

Delauney determines the terms of Phaedra’s slavery by choosing an expensive tattoo artist, and a complicated, expensive custom design. This is a cruelty, for all that Phaedre likes the design. She doesn’t see the exploitation of how that keeps her enslaved longer.

The owners treat children as speculative investments. And manipulate those children into doing the work demanded.

At no point in the first book do we see Phaedre giving an adult’s informed uncoerced consent.

It’s getting a little sickening to watch the characters deconstructed as though their emotions and actions didn’t matter, only the system, so I think I’ll be bailing on this thread now.

At no point in the first book do we see Phaedre giving an adult’s informed uncoerced consent.

is it even meaningful to speak of consent in a world in which your desires can be shaped and mounded by superhuman powers? Phèdre has been designed to enjoy BDSM, so how could she realistically decide whether she wanted to take part in them? It may be impossibl to judge such a world by our world’s standards

Umm, moulded not mounded. Freudian spellchecker

@29, pre-industrial pre-20th Century cultures had no idea of a specific age of adulthood. In many of them, a person would be considered able to provide an informed consent at about 12; it’s not a coincidence that this is the age of bar mitvah, in Judaism, confirmation in Christianity, and other rites celebrating passage into adulthood happen at about that age.

Childhood is a new cultural concept. Except for the very wealthiest of families, children would be “speculative investments.” Historically, children were sent to work in mines or factories as young as four. Powder monkeys on sailing warships could be as young as nine or ten. Naval officers, like Nelson, would usually start their careers by 12 or 13.

The other issue is that, in very few pre-industrial countries, were a parents’ offspring “free agents” even well into adulthood: both Romeo (who was far too young to be married, as he could not be expected to support a household) and Juliet (who was of marriageable age) did not have a right to pick to whom they would marry: spousal choice was an economic and social decision made by the families, not by the couple. (http://staff.camas.wednet.edu/blogs/lindsaypeters/files/2014/11/Renaissance-fact-hunt-articles.pdf; http://www.metmuseum.org/search-results#!/search?q=marriage%20love%20italy&page=1&searchFacet=MetMedia)

@33 – The idea of “no idea of childhood” is a myth. I did a paper on the topic of legal capacity for a European social history class, and there were very clear ideas of what made a person capable of decision making. Age was one factor, as was mental illness, and mental retardation/developmental disability. There were different classes of guardianship, for children without parents, who would age into adult responsibility, for those with incapacity that was permanent, such as mental retardation, and those whose incapacity might come and go, such as mental illness. In each case, the guardian had specific, and different, legal responsibilities for both providing for their dependent and protecting their dependent’s resources for future heirs.

The language used to describe these situations was different from modern legal, medical and sociological language used to describe the situations. But the concepts of incapacity, guardianship, and whether or not one was able to consent as an adult to adult situations and responsibilities was well-understood. You can see these concepts going back to at least the 1300s, and before that, it is more that the historical record thins than that there is evidence that people couldn’t tell the difference in decision-making capacity between children, adults, and adults incapacitated in various ways.

Same thing for “no concept of adolescence.” The word wasn’t in use. But the concept was there. A time between childhood and full adulthood, for learning and preparing for adulthood. Those were the years when children served as apprentices and pages, learning the tasks that would be their livelihood. The years when girls and young women would assemble the household goods that would be their dowry, and that they would later use as adults. When boys and young men would train, and establish their trade credentials.

Even with her unusual kink for pain, Phedre clearly had her desires being manipulated, horribly. We see situations where she wanted to have sex, and had a potential consenting partner, but was prevented by the fact that her owner had a right to sell her virginity. We see that her early sexual experiences are not her learning about what she did and didn’t like with someone who cared about her, but her being put with people not of her choosing, who were not really interested in her emotional welfare.

Without the constraints of slavery, if she’d been able to have an education to support herself in an ordinary way, and the chance to explore and experience her sexuality on her own terms, her life would have been very different.

In a “sex-positive fantasy” you don’t have adults auctioning off the virginity of adolescents. You don’t have children being raised in brothels, knowing that they will “owe” the brothel-keeper a large sum of money, and offered no training or education to make a living except for the training needed to work in the brothel. You don’t have children traded from one brothel to another, based on whether the brothel-keepers think the child will suit their particular clientele.

Phedre’s kink for pain doesn’t take away her human right to choose her own sexual partners – one she is denied from the beginning. It doesn’t change the wrongness of her being sent, as an adolescent, to much older adults, who have the right to do to her what they will, and with her having the right to say “no” only if things get to be too much, but not to work with her sexual partners to explore her sexuality on her own terms and at her own pace.

She doesn’t even get to discover her kink for pain on her own – she is told that she has such a kink, based on her physical appearance. She’s told this from a very young age, as a matter of fact, and it is treated as an absolute, not something where she has the right to decide if she likes pain, and how much, and what types, and with whom, and in what situations. The judgment of Phedre’s sexuality, based on her physical appearance, is disturbing, and calls to mind other sexual stereotypes, such as those based on race, that have caused and continue to cause serous social problems.

@26 Ursula

@25 – What other way did Aleuin have to earn his marque, and his eventual freedom?

There was no marque for Alcuin, until he entered Namaah’s service, unlike Phedre, Anafiel never paid a bond price for Alcuin. I’m not discounting the pressure Alcuin was under to make Anafiel happy by entering Namaah’s service. But there was no marque for Alcuin. I also want to note that AFTER Anafiel learned how Alcuin entered the service despite having no desire to do it, he repeatedly offered to excuse Phedre’s bond debt. She wouldn’t have completed her marque, but she would have been free.

In Re: How long they are indentured?

They are indentured as long as it takes to pay off their marquist. There are cheaper marquist’s, for the Servants who are not in the Night Court. Each Court probably has their own marquist, and the amount needed to pay it off is probably known in advance.

@35 – I’m counting Alcuin as being manipulated into his situation by Delaunay. It was quite clear that Delaunay had a vision of his pair of courtesan-spies, and he didn’t really see Alcuin or Phedre as people who might have other desires for their life. He groomed them, as children, for sexual abuse in adolescence.

And whatever Delaunay later offered Phedre, it doesn’t change the basic problem of having fourteen year old kids making a long-term commitment to work as prostitutes for someone else’s profit. If this happened in real life, we’d call it rape, no questions asked. Fiction is, of course, different from real life, but I’m having a problem stretching the concept of “sex-positive” to include this.

It’s a tough thing to see in a book, because it is all written so beautifully that you don’t realize how badly Phedre is being abused until you really step back from the story to think about it. She’s the POV character, and she doesn’t recognize the exploitation of her situation. In part because she’s a fish in water, surrounded by other children raised the same way, and adults who had been brought up that way, and in part because there is a bit of Stockholm Syndrome around her relationship with Delaunay, whom she sees as rescuing her from the Night Court where she was something of an outsider, and who valued her for something that others saw as a flaw.

@37, until well into the 19th Century, “children” were doing jobs that would be restricted to adults today, including “children” in positions of authority. When he was 12 years old, Horatio Nelson was a serving naval officer who would be expected to lead men into combat, and be right there, in the thick of it. That’s not a job that was assigned to somebody that would have been considered a child by the contemporary society. Nelson was not exceptional in this regard: naval midshipmen usually started by the time they were 14 or 15 years old.

Children had both more and less agency than they do today: 12 year old Nelson commands, albeit as a very junior officer. Conversely, 15 or 16 year old Romeo and Juliet don’t have the agency to socialize outside of bounds set by their parents and grandparents. Both Juliet — probably before she was 17 — and Romeo — probably after he was 25 — would be placed into arranged marriages.

Households — a family and its retainers — had more authority over the action of its members than the do today.

So we’re back to my original question; do we really want to glamorize sexual slavery? Not that it hasn’t been done many, many times before.

As an aside, while I don’t agree with Ursula’s logic, I do agree with her general theme: Phèdre is forced into this life style, and is, by current definitions, abused and, probably by the definition of anyplace within Ms Carey’s world, except Terre d’Ange, forced into sexual servitude. In 2017, barring judicial corruption, the Night-blooming Houses would have been shut down and those in charge imprisoned. On the other hand, Terre d’Ange is not a 21st Century, First World environment.

Phèdre starts as a child who was sold into potential sexual servitude by her parents, indentured to a man whose goal was to make her into a courtesan-spy, and, through the trilogy, goes far beyond being a sex slave.

To be clear, I do love the books. I just have a problem with having them uncritically considered as the 21st century “sex-positive fantasy we need.” Or with treating Terre d’Ange as some sort of sexual utopia.

I’d consider unambiguous, adult, uncoerced informed consent to be pretty basic to anything being sex-positive.

There is value in having stories of people who overcome abuse, even sexual abuse, as Phedre does. But a story of overcoming sexual abuse is something different from a sex-positive story. And telling the story of overcoming sexual abuse in a sex-positive way requires recognizing and naming the abuse, and distinguishing it from positive sex.

This is a story that glorifies sexual abuse and slavery as sexual freedom.

If it doesn’t quite count as a visit from the Suck Fairy when you realize this, at the very least, it goes from being a favorite to a problematic favorite.

Everyone seems to forget that in Kushiel’s Avatar, Phedre begins work on reforming indentureships-

“No more were the Thirteen Houses of the Night Court allowed to see marque-prices for children sold into indenture, such as I had been. Now, it was all apprentices, or such childen as were born into the Night Court and freely raised therein. Anafiel Delaunay would not be able to buy my marque as he did when I was ten….If an apprentice is found unfit to serve, it is meet that the Dowayne of his or her House provides a means for them to serve out the terms of their indenture in the time allotted, no more and no less.” “I am saying the system of indenture as it exists is imperfect. It allows legal means whereby an apprentice may become a virtual slave to his or her House.” etc etc

So obviously Carey was aware of the issues of Phedre’s indenture, as well as the broader issues of the way the Night Court worked. And even has Phedre work to make it so anyone entering the Night Court does it of their own choosing. I don’t think Terre d’Ange is supposed to be a utopia, it’s a complete fantasy world where magic is real and people are touched by the gods but people have very human problems and issues as well. It’s not perfect, and I get some people are still uneasy with the dubious consent in the books. But I think it shows a sexual woman in a lot better light than a lot of other books out there.

@34 Phedre’s desire is not moulded by others due to her features (Kushiel’s dart in her eye). At first no one knows what Kushiel’s dart is, they just consider it an imperfection. It’s only after she’s found out pricking herself with a needle and enjoying it sexually that people in Nereus house recognize what she is (a magical masochist). The first one to mention it is Delaunay and that’s why Phedre’s likes him so much, making her imperfection into something special.

Excellent comments on this thread. I agree strongly with much of what is being said about consent. The way I read the novel without the Suck Fairy is through the lens of first person narration. Phedre is an extremely vivid narrator, and after the first few paragraphs, she ceases to be the quietly bitter older woman of the introduction and is drawn so deeply into the psychology of her own younger self that we may as well be inside the teenage Phedre’s head.

Read this way, I see the novel as being about Phedre’s discovery of real consent. As a child and adolescent, she is conditioned to believe that she lives in a sexual utopia. She genuinely doesn’t understand, for most of the novel, that enthusiastic consent to a specific partner is important. She is completely baffled that Alcuin finds sacred prostitution repellent. But in her encounter with Joscelin, she says straight out “I had never really chosen“. I think that in that line, we see the psychological connection between the teen Phedre and the older author who unromantically calls herself “a whore’s unwanted get”.

You can also draw a fairly straight line between this part of Phedre’s character development and her challenging relationships with autonomy and consent/compulsion with the will of the gods.